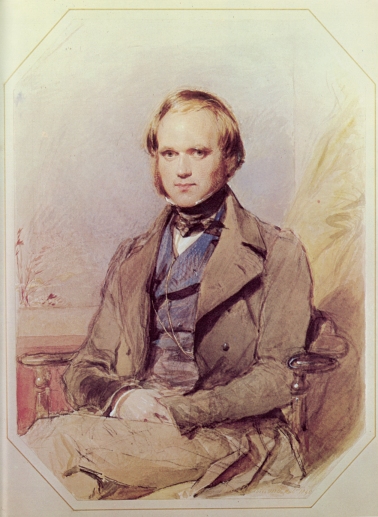

Darwin's beautiful mind, still not fully appreciated

Nicholas Wade's reflections on Charles Darwin upon the bicentennial of his birth and the sesquicentennial of The Origin of Species resonate strongly. It is often said that progress in a science is measured by the speed with which its founders are forgotten. That serious scientists — let alone the American public — continue to debate The Origin and The Descent of Man testifies to the extent to which Darwin was able to accomplish four intellectual breakthroughts that evidently still elude some contemporary scientists:

- Natural selection has no purpose at all.

- Progress is not inevitable.

- Humans are living organisms and therefore subject, all the way down to the workings of the so-called "mind" and all the way up to so-called "culture," to natural selection and sexual selection.

- Group selection applies to humans, too, no matter how willfully humans want to see themselves as individual actors.

It is somewhat remarkable that a man who died in 1882 should still be influencing discussion among biologists. It is perhaps equally strange that so many biologists failed for so many decades to accept ideas that Darwin expressed in clear and beautiful English.

The rejection was in part because a substantial amount of science, including the two new fields of Mendelian genetics and population genetics, needed to be developed before other, more enticing mechanisms of selection could be excluded. But there were also a series of nonscientific considerations that affected biologists’ judgment.

In the 19th century, biologists accepted evolution, in part because it implied progress.

“The general idea of evolution, particularly if you took it to be progressive and purposeful, fitted the ideology of the age,” says Peter J. Bowler, a historian of science at Queen’s University, Belfast. But that made it all the harder to accept that something as purposeless as natural selection could be the shaping force of evolution. “On the Origin of Species” and its central idea were largely ignored and did not come back into vogue until the 1930s. By that time the population geneticist R. A. Fisher and others had shown that Mendelian genetics was compatible with the idea of natural selection working on small variations.

“The general idea of evolution, particularly if you took it to be progressive and purposeful, fitted the ideology of the age,” says Peter J. Bowler, a historian of science at Queen’s University, Belfast. But that made it all the harder to accept that something as purposeless as natural selection could be the shaping force of evolution. “On the Origin of Species” and its central idea were largely ignored and did not come back into vogue until the 1930s. By that time the population geneticist R. A. Fisher and others had shown that Mendelian genetics was compatible with the idea of natural selection working on small variations.

“If you think of the 150 years since the publication of ‘Origin of Species,’ it had half that time in the wilderness and half at the center, and even at the center it’s often been not more than marginal,” says Helena Cronin, a philosopher of science at the London School of Economics. “That’s a pretty comprehensive rejection of Darwin.”

Darwin is still far from being fully accepted in sciences outside biology. “People say natural selection is O.K. for human bodies but not for brain or behavior,” Dr. Cronin says. “But making an exception for one species is to deny Darwin’s tenet of understanding all living things. This includes almost the whole of social studies — that’s quite an influential body that’s still rejecting Darwinism.”

The yearning to see purpose in evolution and the doubt that it really applied to people were two nonscientific criteria that led scientists to reject the essence of Darwin’s theory. A third, in terms of group selection, may be people’s tendency to think of themselves as individuals rather than as units of a group. “More and more I’m beginning to think about individualism as our own cultural bias that more or less explains why group selection was rejected so forcefully and why it is still so controversial,” says David Sloan Wilson, a biologist at Binghamton University.

The rejection was in part because a substantial amount of science, including the two new fields of Mendelian genetics and population genetics, needed to be developed before other, more enticing mechanisms of selection could be excluded. But there were also a series of nonscientific considerations that affected biologists’ judgment.

In the 19th century, biologists accepted evolution, in part because it implied progress.

“The general idea of evolution, particularly if you took it to be progressive and purposeful, fitted the ideology of the age,” says Peter J. Bowler, a historian of science at Queen’s University, Belfast. But that made it all the harder to accept that something as purposeless as natural selection could be the shaping force of evolution. “On the Origin of Species” and its central idea were largely ignored and did not come back into vogue until the 1930s. By that time the population geneticist R. A. Fisher and others had shown that Mendelian genetics was compatible with the idea of natural selection working on small variations.

“The general idea of evolution, particularly if you took it to be progressive and purposeful, fitted the ideology of the age,” says Peter J. Bowler, a historian of science at Queen’s University, Belfast. But that made it all the harder to accept that something as purposeless as natural selection could be the shaping force of evolution. “On the Origin of Species” and its central idea were largely ignored and did not come back into vogue until the 1930s. By that time the population geneticist R. A. Fisher and others had shown that Mendelian genetics was compatible with the idea of natural selection working on small variations.“If you think of the 150 years since the publication of ‘Origin of Species,’ it had half that time in the wilderness and half at the center, and even at the center it’s often been not more than marginal,” says Helena Cronin, a philosopher of science at the London School of Economics. “That’s a pretty comprehensive rejection of Darwin.”

Darwin is still far from being fully accepted in sciences outside biology. “People say natural selection is O.K. for human bodies but not for brain or behavior,” Dr. Cronin says. “But making an exception for one species is to deny Darwin’s tenet of understanding all living things. This includes almost the whole of social studies — that’s quite an influential body that’s still rejecting Darwinism.”

The yearning to see purpose in evolution and the doubt that it really applied to people were two nonscientific criteria that led scientists to reject the essence of Darwin’s theory. A third, in terms of group selection, may be people’s tendency to think of themselves as individuals rather than as units of a group. “More and more I’m beginning to think about individualism as our own cultural bias that more or less explains why group selection was rejected so forcefully and why it is still so controversial,” says David Sloan Wilson, a biologist at Binghamton University.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home